Roopa Gogineni is a Paris-based filmmaker, photographer and curator.

For a decade she lived in Nairobi where she developed a collaborative practice, working alongside communities of resistance across the region. Her films, described as intimate and urgent, have premiered at festivals including IDFA, SXSW, Hot Docs and Sheffield Doc/Fest. I AM BISHA, her documentary chronicling a satirical puppet show in rebel-held Sudan, received the Oscar-qualifying Full Frame Award for Best Short and a Rory Peck Award. SUDDENLY TV, her latest short film about magical thinking and revolution, earned the SXSW Special Jury Award and IndieLisboa Short Film Grand Prize. She has directed documentaries for The New York Times, BBC and Al Jazeera and has led projects supported by the Sundance Institute, Doc Society, CatchLight, Points North Institute, Logan Nonfiction, Firelight and Chicken & Egg Pictures.

Roopa holds degrees from the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Oxford. For four years she supported the PASTRES research program at The Institute of Development Studies as a visual methods advisor and curator. She has taught at Parsons Paris and lectured at Carnegie Mellon and Sciences Po.

She is a co-founder of Sunduq Al Sudan, a collective of filmmakers and artists supporting mutual aid groups on the frontlines of Sudan’s counterrevolutionary war.

awards, fellowships, exhibitions

2023 SXSW Documentary Short Special Jury Award

2023 IndieLisboa Short Film Grand Prize

2021 Logan Nonfiction Fellowship

2021 CatchLight Fellow

2020 Women Photograph Grant Recipient

2018 FRONTLINE/Firelight Investigative Journalism Fellowship

2018 Rory Peck Award for News Features

2018 One World Media Short Film Award

2018 Full Frame Jury Award for Best Short

2017 Firelight Media Short Film Grant

2016 "Over There” Exhibition, Annex Gallery

2016 Exhibition at Women Deliver, Copenhagen

2015 One World Media Awards Short Film Nominee

2014 RISC Benefit Show, Aperture Gallery

2012 Photo Lucida Critical Mass Finalist

2012 Ian Parry Scholarship Group Show

2012 Lucie Foundation Photo Mentorship Program

2012 "The Day I was Destroyed" Exhibition, Annex Gallery

2011 "Coal Colony" Exhibition, St. Antony’s College, University of Oxford

clients

The New York Times | The Washington Post | San Francisco Chronicle | The Guardian | Stern | Capital | Al Jazeera | BBC | TOPIC | Bloomberg | Businessweek | The Sunday Times | The Telegraph | CNN | VICE | Lucky Peach | Eater | NPR | VOA | RFI

THE FUTURE

OF AID

Somali pastoralists have long known cycles of drought and hunger. It was not without precedent when the rains failed in 2016, but then the next two seasons failed as well. They watched entire herds of camels, goats and sheep wither and die. Generations of wealth disappeared within weeks, and hundreds of thousands abandoned their traditional rangelands for IDP camps in urban centers, where a new aid paradigm emerged. Instead of distributing traditional food aid, which floods local markets with agricultural surplus from western countries, humanitarian agencies began sending mobile cash transfers to displaced people so they could spend according to needs.

Cash transfers now reach an estimated quarter of Somalia’s population. While transfers do little to address the underlying climate conditions, conflict, and political failings that can lead to famine, they may have the ability to stave off the worst hunger crises, and could be the first step towards universal basic income in Somalia.

These photos, taken in a photo booth set up in a camp for displaced people, capture how people use the $60 they are sent every month.

KENYA’S MODERN APPROACH TO OPIOID ADDICTION

East Africa’s emergence as a major drug smuggling hub has led to an explosion of heroin use in the region. While Kenya’s government has largely failed to crack down on trafficking, its response to addiction has seen success. It is one of the few African countries to implement harm reduction strategies, such as needle exchange or drug replacement therapy, which remain controversial in many parts of the world.

I am from West Virginia, which has the highest opioid overdose rate in the US. The patterns I saw in Kenya were achingly familiar. People talked about the nearly instant physical addiction, the lies they told to family, the pawning and stealing, the crippling pain of withdrawal. The same stigmas exist in both places, as does the fight to redefine heroin use as a public health crisis, instead of a criminal problem.

These photographs tell the story of recovery in Kenya, that could be the story of recovery anywhere.

Photographed for Open Society Foundations.

ON THE LIDO

Ever since fundamentalist al Shabaab militants were chased from the city by an African Union peacekeeping force in 2011, Lido Beach has become a trope for peace, the stage for Mogadishu’s renaissance.

The film Jaws was released in the summer of 1975. It slowly made its way to beach towns around the world, inspiring nightmares and cementing sunbathers to the sand. When Jaws arrived in Mogadishu, Somalia, people might have thought New England was a nearby place, and even that the film was about their own town.

Between 1978 and 1987, 30 shark attacks were documented off of Mogadishu’s famous Lido Beach. All but two were fatal. The construction of a new port had broken through coral reefs, allowing bull and tiger sharks to come closer to shore. Most of the fatalities occurred in the summer months of the monsoon, when the salinity of the water attracted even more sharks. During these years, the rains coincided with Ramadan, just as the abattoir up the coast went into high gear, throwing entrails of goats, camels, and cattle into the water.

Mogadishu in the 80s was a capital of wide, tree-lined streets, coral-stone homes, and a famous Indian Ocean breeze. Since it was settled around a thousand years ago, it has occupied a space at the crossroads of the Mediterranean, African, Asian, and Arab worlds. The openness of its people, a seaside virtue, is on display at the beaches, especially along popular Lido, in the center of town. Back then, a running club met once a week there. Somalis and expatriates jogged together in shorts, the women unveiled. Stalls lined the street behind Lido where kids would sell sea exotica and ivory. Beach clubs dotted the stretch of sand, where you could have lunch on the deck and watch people wade into the water.

The slaughterhouse along the coast that brought the sharks was always busy. Somali society centered on livestock, especially camels; despite having the longest coastline on the continent, Somalis never ate much fish. President Siad Barre, who had come to power in a 1969 military coup, set about establishing fishing cooperatives and declared two days of the week as fish-eating days to stave off food shortages.

Eventually, Somalis tired of Barre’s brand of scientific socialism. In practice it came to focus more on elaborate displays of statehood—constructing dozens of monuments and organizing regular parades—than on the actual workings of a state. His style of management stood at odds with the population he sought to control, for which self-reliance and private enterprise has always reigned. Finally, mired in corruption and weakened by several clan-based armed opposition groups, the government fell in 1991. Barre fled the country, and the national army dissolved. So began a war whose end we have not yet seen.

Divisive clan politics laid waste to Somali society, and a catastrophic famine accompanied state collapse. More than 300,000 people died of hunger the following year, prompting the first of many botched international interventions.

One morning before dawn in December 1992, more than 100 foreign journalists waited on a beach just south of Lido. They watched the dark ocean, looking for signs of a supposedly secret US Marines operation intended to pave the way for food distribution. A CBS news crew caught the arrival of the advance reconnaissance team with night-vision scopes, and they broadcast it live. “This is literally a three-ring circus here on this beach right now,” a captain shouted over to the press corps.

For the next 20 years Mogadishu’s beaches were quieter. People stayed indoors, fearful of spontaneous firefights that pockmarked the city’s white coral walls and left rubble in most streets. Breaks in the violence never lasted long.

In January 2014, the peace on Lido did not feel like a mirage. Facing the sea, my back to the ruins, I could almost touch it. The throngs of people were thick, and walking through them made me think it would be impossible to feel lonely in this city, if only because of the beach. It was Friday, a holiday, and everyone was here.

Photographed with Trevor Snapp for VICE Magazine.

“Castration Rock,” Lukenya, Kenya

THE DAY I WAS DESTROYED

Just after christmas in 1957, colonial officers stopped a bus Naomi Kimweli was riding with her family outside Nairobi, Kenya. They separated her from her three children, blindfolded her, beat her, and raped her with a bottle. Nearby they castrated her husband with a pair of pliers. She never saw her children again. That, she tells me, was “the day we were destroyed.”

.

The abuses were part of a systematic campaign of torture to suppress the Mau Mau uprising. Panicked colonialists detained over one million Kenyans, most of whom had nothing to do with the guerrillas. Naomi did not think the men who abused her would ever be held accountable. But in 2005, researchers uncovered a hidden archive of colonial records in London. Naomi’s story, and thousands of others, found new footing.

In 2012, Naomi and three other Kenyans traveled from their villages to testify in the British High Court on Fleet Street. They were the face of a historic class action lawsuit seeking both a formal apology and reparations for colonial era abuse. Fifty five years after Naomi’s bus was stopped, the British government settled out of court and agreed to compensate 20,000 Kenyans.

THE VILLAGE

DOCTOR

At 92, my grandfather still spends seven days a week in a rural clinic he set up in 1951 after serving as a doctor in the Indian army. His work and life were forever shaped by independence era ideals of secularism and internationalism. He trained his hospital staff, most of whom had not completed high school, in medicine and Marx. He was not alone in his thinking, but as decades passed, a fervent religiosity spread. India recently elected a far right Hindu nationalist as Prime Minister. Men and women like my grandfather became relics. These photographs are a portrait of a man and a place stuck in time. They capture his vague loneliness, surrounded by people, but in a country that has grown strange to him.

COLLISIONS

in post-productionEvery year more than 80,000 meteorites crash into earth. Many land in the stark Saharan sands, where they are spotted by passing nomads. Some are worth far more than earthly gold, others contain clues to the deep history of our solar system. Now everyone is looking.

Produced for BBC Arabic.

SUDDENLY TV

قناة فجأة

In April 2019, a nonviolent youth-led movement in Sudan toppled the genocidal military regime that had been in power for three decades. After the fall, Sudanese from across the country made their way to Khartoum to demand a peaceful transition to civilian rule. There they formed a sit-in protest, where art became the means to conjure a new Sudan. Having known nothing other than state-sponsored propaganda on TV, a group of young revolutionaries perform an alternate reality as a roaming television news crew.

in partnership with Al Jazeera Witness and Gisa Productions

World Premiere - IDFA 2022

North American Premiere - SXSW 2023

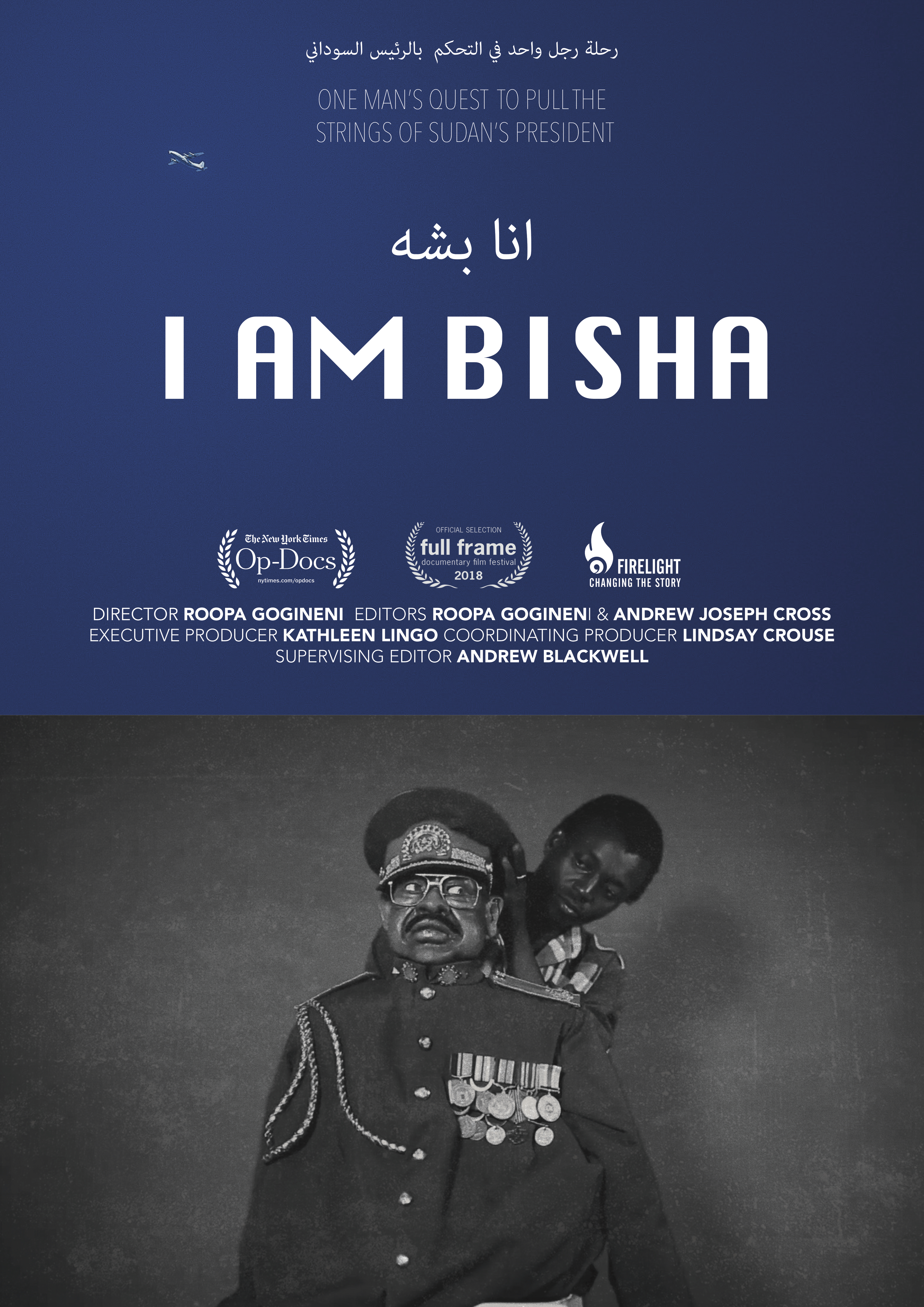

I AM BISHA

Over the past seven years, Sudanese president Omar al-Bashir has dropped thousands of bombs on villages across the Nuba Mountains. Ganja, the 26 year old pacifist son of a rebel commander, witnessed a bomb drop meters from his home. He has never found a way to fight back- until now.

Ganja became President Bashir. Or to be precise, he became the man who controls Bashir’s head. Ganja and his friends in the Nuba Mountains acquired a puppet of the dictator and filmed a satirical web series called “Bisha TV.” The show follows the president’s schemes to raise money for a campaign of violent suppression across Sudan. Over one million people have watched “Bisha TV,” most of them inside Sudan.

This short film (14’) weaves together the story of Ganja’s life in the Nuba Mountains, his creative process working under extraordinary conditions, and darkly hilarious scenes from “Bisha TV.” Through Ganja’s work- and the comic escapades of two Sudanese strongmen- we see an unlikely flowering of political humor and appreciate the true power of grassroots media.

-

Distribution: Good Docs

Recognition:

- Rory Peck Award for News Features

-

One World Media Short Film Award

- Full Frame Jury Award for Best Short

Festival Screenings:

- Full Frame Film Festival 2018, World Premiere

- Hot Docs International Film Festival 2018, International Premiere

- Sheffield Doc/Fest 2018, European Premiere

- Original Thinkers 2018

- Hamptons International Film Festival 2018

- IFC Center Screening 2018

- SF Doc Stories Screening 2018

- IDFA Docs for Sale 2017

- IDA Screening Series at LACMA 2018

- Foreign Correspondents Association of East Africa 2018

- ReFrame Film Festival 2018

- JAYU Human Rights Film Festival 2018

- Waging Peace, Sheffield 2018

- Footcandle Film Festival 2018

- 41 North Film Festival 2018

- FIPADOC 2019

- FIPADOC Retrospective Days at Biarritz Library 2019

- MUICA Film Festival (Colombia) 2019

- International Documentary Film Festival of Bogotá 2019

- The Media Majlis at Northwestern University 2019

- Gracias Africa (Colombia) 2020

- The Never Again Coalition, Rising Up: Sudan 2020

- Wallay Festival (Spain) 2020

- Society for Photographic Education (SPE) Media Festival 2021

PRESS ︎︎︎

THE WALL

A massive security wall divides the city of Mogadishu, Somalia. On one side, millions of Somalis live with the daily threat of violence. On the other side is a UN compound that houses international diplomats, aid workers and peacekeepers. Movement between these two worlds is severely restricted. What do people imagine is beyond the wall? Made for AJ+.

PORTRAITS OF

MOGADISHU

For a generation, the lives of young Somalis have been obscured by violence. Today, the fragile peace in Mogadishu allows youth to imagine a future beyond war. Made for VICE.

Nominated for a One World Media Award in 2015.

Nominated for a One World Media Award in 2015.

A CONFEDERATE

RECKONING

Can we reconcile different versions of history? Two American foreign correspondents of color fly from Kenya to Louisiana to report on an unfinished civil war back home. Made with Michael Onyiego for WVBP’s Us & Them Podcast.

Selected by The Atlantic as one of ten great podcasts from 2015, and as part of the Podcast Listener’s Guide to the 2016 Election.

MUZAMIL'S DAY

In this special episode for kids, FRONTLINE follows a day in the life of Muzamil, a 12-year-old Somali boy growing up in Kenya’s Dadaab Refugee Camp. Producer Bianca Giaever and Reporter Roopa Gogineni bring him questions from American kids about what it’s like growing up in a refugee camp. Are there dentists? A fire department? What is your dreamland? Muzamil takes us through his daily life, answering questions from American kids along the way.

THE OTHER

REAL WORLD

Reality TV may be popular around the world, but it's also roundly mocked

as formulaic and contrived. So, can that kind of fragile fantasy world

meaningfully influence reality? We look at the goals and impact of a

UN-backed reality show called "Inspire Somalia," that attempted to model

democracy and freedom in a country racked by decades of clan warfare

and oppression by extremist groups like al-Shabab.